Featured Harp Guitar of the Month

by Gregg Miner. July, 2007

| This is an updated version of my

Winter, 2006

Guitarmakers article entitled “The First True Harp

Guitar.” Missing from the

printed article were the footnotes, without which some of the critical

context, supporting evidence and reasoning (and humor - this is

supposed to be fun, after all) was lacking.

Additionally, I was able to finally obtain two clues pertaining

to the use of the “harp guitar” term abroad before

the appearance of the American instrument featured below.

Thus I changed my title, which was, and is still, meant to read as

a semantic riddle. And what

exactly then do I mean to imply by this statement?

First of all, it will help if readers are already familiar with my long-winded dissertation “What is a Harp Guitar?” published in the Historical section of Harpguitars.net. In it, I attempt to define - for the first time, and hopefully once and for all - what delineates a harp guitar, as we use the term today.[1] There are loads of factors in deciphering why certain instruments can be considered harp guitars and others not. Likewise, there are reasons (some valid, many misguided) why most harp guitars were (and are still) called by other names, and why some well-known historical instruments labeled “harp-guitars” are something else entirely. Confused? Understandable, and unfortunately we won’t be able to resolve it in this article. |

|

The simplest, bottom-line modern definition of a “true” harp guitar (meaning my modern typology or classification term) that I can give you is this: A

guitar, in any of its accepted forms, with any number

of additional unstopped strings that can accommodate individual

plucking. To elaborate; the word "harp" is now a specific reference to the unstopped open strings, and is not specifically a reference to the tone, pitch range, volume, silhouette similarity, construction, floor-standing ability, nor any other alleged "harp-like" properties. A true harp guitar must have at least one unfretted string lying off the main fretboard.[2] Further, while these open strings may sympathetically resonate, they are meant to be played. Beyond that, literally almost anything goes regarding construction, form, stringing and tuning. |

|

The Hansen Harp-Guitar So far so good? Then let us move on to our featured instrument: Hans J. Hansen’s harp-guitar, made in Chicago and patented in 1891.[3] It clearly qualifies according to the current definition, thus it is a “true” harp guitar (ergo its use in the title). So what do I mean then by “first”? Surely there were other harp guitars throughout the world before this instrument was built (yes, many thousands). No, it is not the instrument, it is the name. The noteworthy feature of this instrument is that – it was the first true harp guitar to actually be called a harp guitar.[4]

A problematic paradox of the whole study and discussion of harp guitars is that none of the earlier instruments ever actually used the term.[5] Even now, they are only slowly being thought of as harp guitars, by those accepting of my proposal to retroactively apply the currently accepted definition of the last hundred years to instruments of the preceding centuries (when there was no need or concern for classification). As this is still an uphill battle, I was glad to find that Hansen used the name both in his patent and on the labels in his instruments. Why he chose to use the term, and whether it had been applied to these instruments prior to his patent is a remaining question, which future discoveries may answer.[6] Just five short years after Hansen, another

American (transplanted from I have to give Knutsen credit for working his magic seemingly in a

vacuum in the |

|

|

The

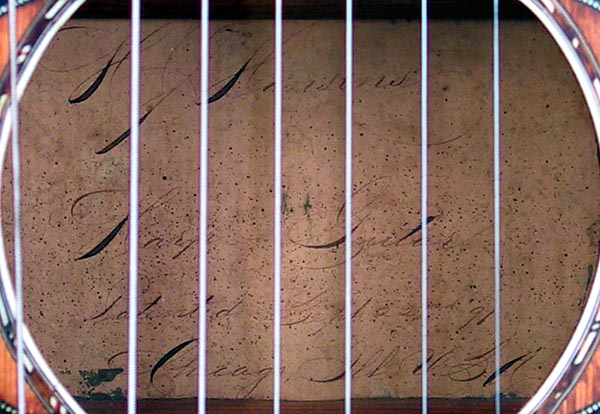

Patent Patent # 459,932 was filed on Feb 3, 1891 and granted on Sept 22. As stated earlier, the Hansen patent contains the first documented American use of the term “harp-guitar” to actually refer to a true harp guitar. Even the most unusual instrument patents invariably were simply titled “Musical Instrument,” “Guitar” or, if especially descriptive, “Stringed Instrument.” It was left to delving through the often mind-numbing text for clues as to what the inventor was proposing to call his instrument. Most often, the patents are insufficient, and the only option is to locate advertising material or a specimen with a label. So I tip my hat to H. J. Hansen, who kindly provided both! His patent clearly states “to be called a ‘harp-guitar’.” In addition, the extant specimen has a very faded, but exquisite label which reads: |

|

H.

J. Hansen’s |

|

And not only to we have proof positive about what a harp guitar was in 1891, Hansen even helped defined it for us! His patent mentions the fact that the sub-bass strings are plucked (important only because there are still some today who think sub-bass strings were only added for sympathetic vibration), and also states: “….bass strings, from 1 to 6 in number.” It had taken me many weeks of soul-searching and hitting-the-books before I came to this same conclusion - committing to the idea that just one floating bass string can (and must) qualify a guitar as a harp guitar. I don’t think anyone had previously discovered or recognized that Hansen had attempted to establish the obvious all along! If this doesn’t get the hesitant argumentative scholars and organologists off my back, I suppose nothing will.[9] |

| The patent has several features, but the two

key features are the bass “harp strings” and a non-pin bridge to eliminate

drilling holes through the guitar’s top.

|

|

The

Specimen Besides its historical importance, this is one rare guitar! The only Hansen instrument I have ever seen or heard of, it was acquired by Intermountain Guitar & Banjo in Salt Lake City in the spring of 2005 (if anyone can find a harp guitar, they can). It is wonderful and unique in many ways. Right off the bat, it’s obvious that Hansen very accurately followed his patent – or perhaps the reverse, the patent being drawn from this actual instrument (it’s surprising how many patents were not only obviously created before-the-fact, but were even technically un-producible).

The instrument has four harp strings like the patent, suggesting that this was Hansen’s preferred number of sub-basses. I tune them in descending order D, C, B & A, a standard tuning for “ten-string guitars” (harp- or otherwise). The bass headstock design is unique and quite attractive, supported by a square wooden post reminiscent of those on fancier concert zithers.

The main headstock is a fascinating three-dimensional affair,

unlike anything I have seen before.

With Brazilian rosewood back and sides and exquisite

soundhole inlay consisting of an intricate design of pearl, ebony and

delicate purfling, this is quite a fancy instrument.

And all in all very classy, until Hansen gets to the fingerboard,

with its rather ostentatious pearl inlays.

Looking at all the intricate and varied purflings and inlays, one

can imagine Hansen ordering from one of those wonderful and exhaustive

1800’s German guitar materials catalogs like a kid in a candy store.

Other motifs on the instrument are rather nice, like the

headstock inlay and celluloid Cupid with horn on the pillar.

It is not known if Hansen built instruments himself

or contracted someone else to do so. Guitar expert Frank Ford (who

photographed the instrument) opined that the craftsmanship, and

especially symmetry, of the body suggests that Hansen likely

commissioned one of the better

|

|

The

Provenance In my thirty-plus years of research, I have found nomenclature and classification to be a very inexact science. On the other hand, I suppose we’re lucky that it has never become an exact science – it would be pretty awkward if musical instrument organology was held to the same “first name” rule that ruined “Brontosaurus” for so many school children (and me).[10] The sidebar below contains two good examples that illustrate how inventor’s names for their instruments can sometimes cause future confusion. For us to stay apace, I believe we need to research, discuss and categorize these instruments that were built one, two or three hundred years ago not only from their historical perspective, but in context with the whole of history, up to the present day. The historical inventors and builders couldn’t have predicted the duration of their creations’ musical lifetimes, nor imagined what might come centuries later. Nor is it easy, or sometimes even possible, for modern researchers to obtain all the necessary analytical clues from the past. Hansen’s 1891 instrument is a compelling piece of nomenclature provenance that should help tie the harp guitar’s past and present - and increasingly bright future - together. |

|

||||||

|

Photos by

[1] To fully absorb my “thesis,” you’ll need at least an open 3-day weekend and a good strong pot of coffee. Then, assuming you get through it, you’ll need to call me so we can further discuss the particulars and go through all those tedious but essential footnotes (for which I will need my own pot of coffee). [2] Notice that I didn't say "lying off the neck." While the majority of harp guitars have their sub-bass harp strings lying well off the neck, some, such as those by Lacôte, are positioned directly over an unfretted portion of a single neck. [3] To hyphenate or not to hyphenate? Both are acceptable spellings, and may be considered interchangeable. In truth, “harp-guitar” (with a hyphen) is more traditional, having provenance in most cases by the inventors, manufacturers and distributors who described their instruments (admittedly with random and inconsistent exceptions). At some point in the last couple decades, writers, players and aficionados started dropping the hyphen (perhaps an aesthetic choice?). As I was just about the only guy on the planet adhering to the hyphen, I finally gave in – using “harp guitar” in all but certain specific instances.

[4]

At least in

[5]

Original terms for instruments I now classify as harp guitars (translated

into English) include: theorboed

guitar, bass guitar, contra guitar,

contrabass guitar, “bow” guitar, Schrammel

guitar, and in many cases, simply 7-,

8-, or 10-string guitar. [6] Foreign language equivalents of the term “harp-guitar” (most often German, as in gitarrenharfe) have been used for certain true harp guitars built long before 1891, but to my knowledge, there is no provenance attached to any of them – only a later applied term by a museum curator or scholar. Nor have I discovered any earlier non-American harp guitar patents or catalog references. The closest we come is a reference found by Russian guitar historian Oleg Timofeyev. In an 1871 Russian ad for Mark Sokolovsky's concert this statement appears: "2. Duet na russkie motivy ("Chem tebia ia ogorchila" i final "Po ulitse mostovoi") soch. Sora, isp. na dvukh arf-gitarakh g. Sokolovsky and g. Shokhin." Timofeyev translates this as: "a duet on two Russian songs ("How did I upset you" and the finale "Along the street"), comp[osition] by F. Sor, to be performed on two harp-guitars by Mr. Sokolovsky and Mr. Shokhin." I would agree that this is indeed an earlier use of "harp-guitar" - the $1000 question is where did the term come from? From one of the two performers? The ad writer? The builder of either of the instruments? Were these doubleneck "bass guitars" – as typically used in Russia - or hollow arm instruments? If the former, were they now known in Russia as harp guitars - or was this a one-time occurrence? Even more striking is the 1848 appearance in Europe of the term Harfengitarre – which appears in a review of a performance by Mertz in reference to a guitar with four extra bass strings. This incredibly important clue comes from Alex Timmerman (Ivan Padovec, 1800-1873 and His Time, p.119). The form of instrument is not known, and Timmerman speculates that it "could well have been a prototype of the ten-string 'Bogengitarre' ('Bow-guitar') later developed and built by Friedrich Schenk." Timmerman brings up an excellent point. As the “theorboed” Staufer and Scherzer style of harp guitar would later be colloquially referred to as “bass guitars” (a term Timmerman and others steadfastly adhere to), it is logical to look for another instrument candidate, and the hollow-arm bogengitarre is a good one. “Bogen” (“bowed” or “arched”) refers to the hollow arm extension; coincidentally, Knutsen would refer to his very similar 1896 American invention as a “harp frame” or “harp shape.” It is indeed tempting to postulate this scenario, even though it would make our naming conventions – and much of my organological premise – much more difficult to investigate and organize! (i.e.: implying a possible historical convention of vernacular naming separation between two main forms of harp guitars: the Schenk-type hollow-arms and the Scherzer-type theorboed/double-neck instruments). Until we are able to resolve this key question – which may be never – we can only make readers and researchers aware of it. The other important part of this provenance – whichever instrument it referred to – is where the term came from. Did the reviewer invent it? Or was it announced by Mertz or in the program as a harfengitarre? Unless we can trace this provenance down, we can’t really consider this a “formal” historical term, and so far it appears to be the only reference in Western Europe throughout the entire 19th century. This is fascinating and important history here, as we continue to search for the real "first true harp guitar"! [7] I know – it gets tricky because Knutsen also made hollow-arm guitars with no extra strings, which he would also call “harp-guitars” - just as Dyer would later call their hollow-arm mandolins “harp-mandolins.” While accepting the validity of this historical name, we must be careful to clarify these as pseudo harp guitars or hollow-arm guitars for purposes of more precise modern classification.

[8]

Even through the 1920s many

[9]

I’m teasing (and baiting) my fellow

scholars here. We “agree to

disagree” and only argue because we care. Actually, there might be one or two who may never even agree to

disagree….such is life. [10] “Brontosaurus” was discovered decades later to be the same as a previously named dinosaur – the very un-Flintstones-like Apatosaurus - which the beast must now be called. |

|

Harp Guitar of the Month: Archives |

| Collectors,

Authors, Scholars: Want to create a page about a certain harp guitar

maker or instrument? Contact

me!

|

|

If you enjoyed this article, or found it

useful for research, please consider making a donation to The

Harp Guitar Foundation, |

|

|

|

All Site Contents Copyright © Gregg Miner,2004-2020. All Rights Reserved. Copyright and Fair Use of material and use of images: See Copyright and Fair Use policy. |