Note, 11/13/2020: I revamped this post after receiving much feedback from luthiers about black walnut examples. I hope here to better clarify the intent of this post – which is not about the varied “pretty walnut sapwood color and figure” but about confirming the wood used in an Orville Gibson harp guitar, which – due to his 100+ year-old stain and finish – shows no color difference. One really needs to have held the Orville in their hands. In lieu of that, I’ve included some additional photographs below.

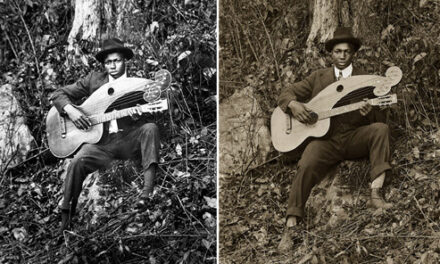

In 2018, my piece on Phil Rowen’s original Orville Gibson harp guitar appeared in The Fretboard Journal #41.

I then followed that up with a blog that included much more detail on the construction of the instrument. Both addressed Orville’s “mystery wood” that has the unassailable appearance of walnut in one area but the irrefutable look of mahogany in another – with no seam in-between! Here’s what I last wrote about it in March 2018 (with no one taking the bait):

Despite all efforts, I was unable at the time to get a consensus from professional luthiers about the woods used in the instrument. Aren’t mahogany and walnut completely different?! You would think so, but there are large chunks of wood that Orville used that give the appearance of seamlessly transitioning from walnut to mahogany, which was botanically impossible last time I checked.

Back to 11/20: Here’s an image of the back from the outside and inside illustrating the “mahogany grain” that was confounding us (click to expand, I made pretty large images). Of course, the uniform red color didn’t help any; through the soundhole you can see the bare wood. (The cropped illustration from my Joinery Mockup points out the back seam at right.)

Back to 11/20: Here’s an image of the back from the outside and inside illustrating the “mahogany grain” that was confounding us (click to expand, I made pretty large images). Of course, the uniform red color didn’t help any; through the soundhole you can see the bare wood. (The cropped illustration from my Joinery Mockup points out the back seam at right.)

Again, the neck and sides of Orville’s harp guitar – carved and joined from giant slabs of something – all had small to huge areas of this “mahogany grain.” For the last 2-1/2 years, I never heard a peep from anyone commenting on the wood(s), though it may be that “those in the know” missed the two articles or didn’t make contact.

Then, recently (early November, 2020), an FJ reader wrote me with a wonderful, detailed story – and evidence – that beautifully answered the question and resolved the mystery. With his permission, I’m sharing the entire narrative so no details are omitted. (Italics are mine.)

“Hello, Gregg. I’m not a harp guitar guy, but your piece in F.J. 41 was highly entertaining and engaged my curiosity about old Gibson instruments and how they were put together. The mahogany/black walnut question is something I’d run into before. Back in the 70’s my father swapped a truckload of Douglas fir firewood for a couple of black walnut logs. The logs came from an old orchard near Lebanon, Oregon. The orchard was being cleared for housing development and the developer was cutting up the walnut logs for firewood. He complained to my father that the walnut didn’t burn very well. I helped my father mill the logs into slabs. He never got around to his furniture building projects and he gave me the lumber about thirty years ago. I got the urge to build myself a pile of guitars a few years back, riffled through my wood stash and started milling up the black walnut. I had no idea of the range of color and figure in this stuff. It ran from chocolate to black coffee to purple to cream to, well, something red that looked and worked exactly like mahogany. The photo below is of a resophonic guitar I just finished and shows the range of color pretty well. It has super-blond shellac on there, so the color is not modified much by the finish. The rib is a piece of the above mentioned walnut, the binding is fumed tiger maple, and the endpin is plum (more orchard salvage).”

“One thing I’d wondered about this salvaged black walnut is that the orchard trees are English walnut branch stock grafted onto black walnut trunk and root stock. The notion being “who wants to actually try to crack open and eat a black walnut?” and yet the trunk and root stock of a Black Walnut tree is much hardier than the English walnut tree. This grafting is, or was, standard orchard practice. I’d noticed in slabbing this stuff up that as the trees grew the area around the graft had color migrating both up and down: English walnut into black walnut and the black walnut up into the English walnut area. I’ve no idea how this may have affected the coloring in the wood of the whole tree. One question always leads to the next one…

“Thanks for your web site and your articles. Regards, Steven Kennel”

Addendum: As mentioned above, many later commented on the “sapwood” of black walnut, but in this case, we’re talking about (my new discovery of) grafted walnut. Reader Neil Harrell subsequently located this image of a walnut orchard that shows “English on top of Claro or Black walnut I would guess. Boards from these trees would be unusual to say the least.” Indeed!

I think Anthony Powell had guessed something along these lines when he saw the instrument, and perhaps others knew of this phenomenon as well.

Kathy Wingert responded that “Many Northern California builders use a lot of walnut. Lance McCollum used it all the time. It was well-known among the NorCal builders that the transition is because most of the walnut is coming form orchards. Walnut trees have a 1 in 4 chance of producing good tasting nuts, so the better tasting, genetically selected English Walnut is grafted onto black walnut (or the other way around).”

And John Bushouse wrote this: “Have you seen the ‘grafted walnut’ line of guitars Taylor made in the mid-2000s? The backs (or tops, on electrics) feature the graft line. Some of them are stunning. I don’t see any pics on the Taylor website, but there are a number of them for sale online, and the listings have pics.”

My friend Kevin Stevenson also mentioned his stunning Kevin Ryan guitars which used grafted walnut.

All I can say is: Cool. But where were all of you in March, 2018?!

Anyway, a picture (and clear explanation) is worth a thousand words, so Steven, thanks for sharing and solving my mystery. (and nice resonator guitar, as well!)

Hi, Great piece ! I have it in my head from wood science lectures at college (35 years ago!) that timber can be accurately identified as a species from magnified examination of the end grain. This would be impossible for a guitar body but the headstock top could be done…maybe.

M