Last week I took you through my personal first time tour of the very impressive National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota. I was there to attend the annual meeting of the American Musical Instrument Society – and will share here a brief recap of my experiences, so you can meet some of the other members and get a taste of what goes on at these conventions. By the way, anyone can join the society and come to these events (you needn’t be a “scholar,”), so don’t be shy!

After our delightful cocktail evening in the foyer of the museum on Wednesday night (with the whole museum open to us), it was up the next day bright and early for a full day of papers. For the uninitiated, “papers” are academic research projects that were once disseminated on actual paper, but are now typically presented orally with PowerPoint and other visual and audio aids.

Some gamely sit through each and every one; I admit I do not. One normally attends those in their area of interest, then a few other snoozers to be polite. Nonetheless, one never knows what one may get out of a topic with, say, the eyeball-glazing title of “Arsene Lecomte, Charles Jean-Baptiste Soualle and the Saxophone Octave Mechanism in the Nineteenth Century.” (It was surprisingly interesting, as a lot of this stuff is, once you become a teeny bit familiar).

I have rarely made it to the first paper of the morning/week at these AMIS meetings (worse than getting up in the morning at our Gathering!) – but made an effort as “The Finds of a Curio-Hunter: Frederick Stearns and His Collection” sounded right up my alley. It turns out, Stearns was pretty much exactly like me (a hundred years ago), but with money. A lot of money. Anyway, the paper was given by my colleague Chris Dempsey (whom I met at last year’s Boston event), who was until recently the curator of the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments at the Ann Arbor University of Michigan (I know – these things end up in the oddest places…). There is a ton of wonderful stuff there (which I’ve never seen – not many have); unfortunately it continues to languish as the school’s poor orphan child.

Luckily, Chris retained a lot of information and files when he left, and he shared some of the stories and images with us. I was as fascinated by Stearns’ natural history collecting as by the instruments; he traveled the world looking for treasures that few were doing at the time. (Think 1300 musical instruments are impressive? Try counting his mollusks.)

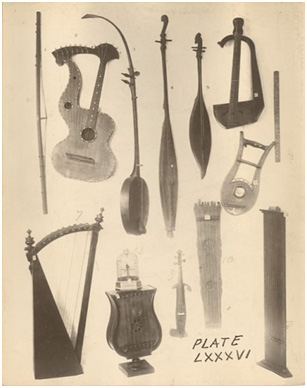

Gulping down coffee and trying to absorb all this, I almost missed a couple of incredible images flashing across the screen. Here’s just one teaser, a catalog page from Stearns’ 1900-1901 European collecting trip. I’ll do a follow-up story on a couple intriguing new harp guitar finds shortly.

Lesson learned: You just never know what you might discover at someone’s lecture (thanks, Chris!).

Other papers I found particularly interesting or helpful to my own little plucked strings hobby included:

“Mordaunt Levien and the influence of French Guitars,” by my friend Hayato Sugimoto, who (like Taro Takeuchi recently) has taken the study of the Harp-Lute family very seriously. He claims my simple little page on Harpguitars.net (under “Relatives”) helped inspire and inform his research. That’s nice of him, but his doctoral research is now educating (and correcting!) me. He just finished his thesis “The Harp-Lute in Britain, 1800-1830” and gave me a copy, which I now have to find time to read and digest.

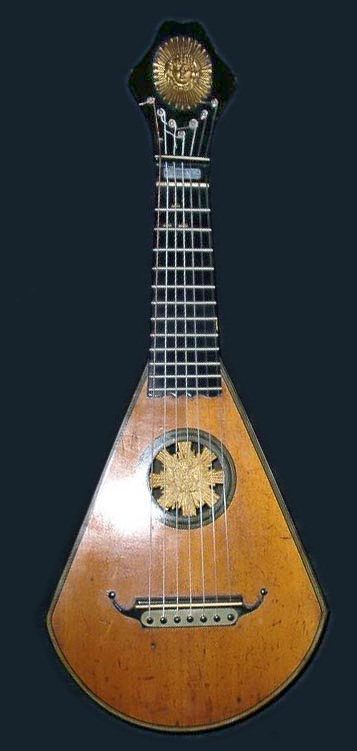

Here’s one of Levien’s Guitare-Harpes (yes, the name has a long and complicated explanation…). Hayato explored his harp-lute development in France (Levien was actually English, and inventor Edward Light’s main competitor).

Musicologist and bow maker Matthew Zeller from Duke University talked about the NMM’s Amati ‘King’ Cello (the earliest bass instrument of the violin family known to survive), a fascinating and thoroughly detailed illustrated paper about the “reduction” of the mid-16th century instrument (I guess I never thought about how these precious instruments were aggressively “modernized” for the next century’s musical tastes (presumably into a new precious instrument – but, still!).

The following day, Matt walked us through the details again while we could all inspect it firsthand and ask more questions.

I mentioned Jonathan Santa Maria Bouquet’s restoration last week. Jonathan (here with his wife Sarah Deters, both now at the Edinburgh Museum) talked about the “self-destructive construction elements” in 19th century guitars, and the challenging aesthetic and ethical decisions in preserving them.

It gives me more food for thought as I try to make my wonderful but crappily-built Knutsen harp guitars playable…

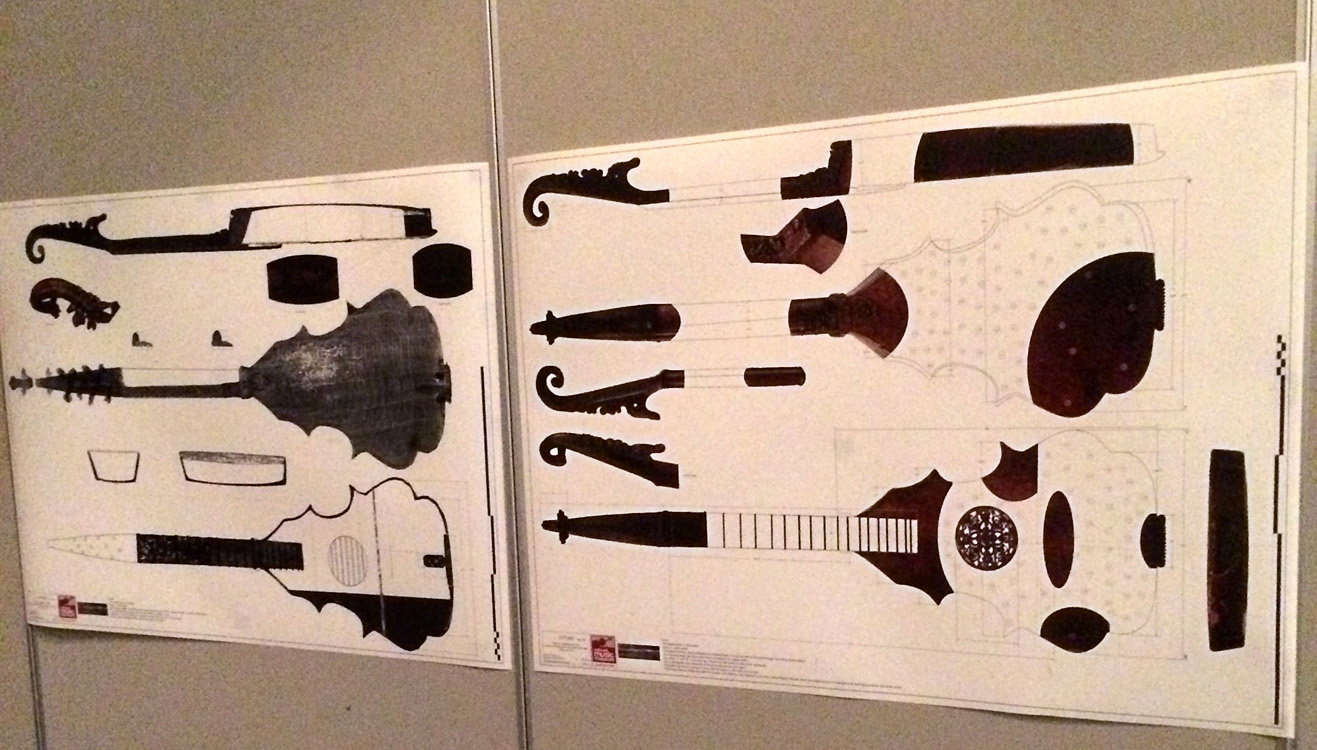

You remember that cittern I was enamored with in the last blog. I was thus delighted that USD grad student Esteban Marino Garza gave a paper on it (investigating its attributed Urbino, Italy provenance). Afterwards I had to check out the beautiful new plans of the instrument he’d done.

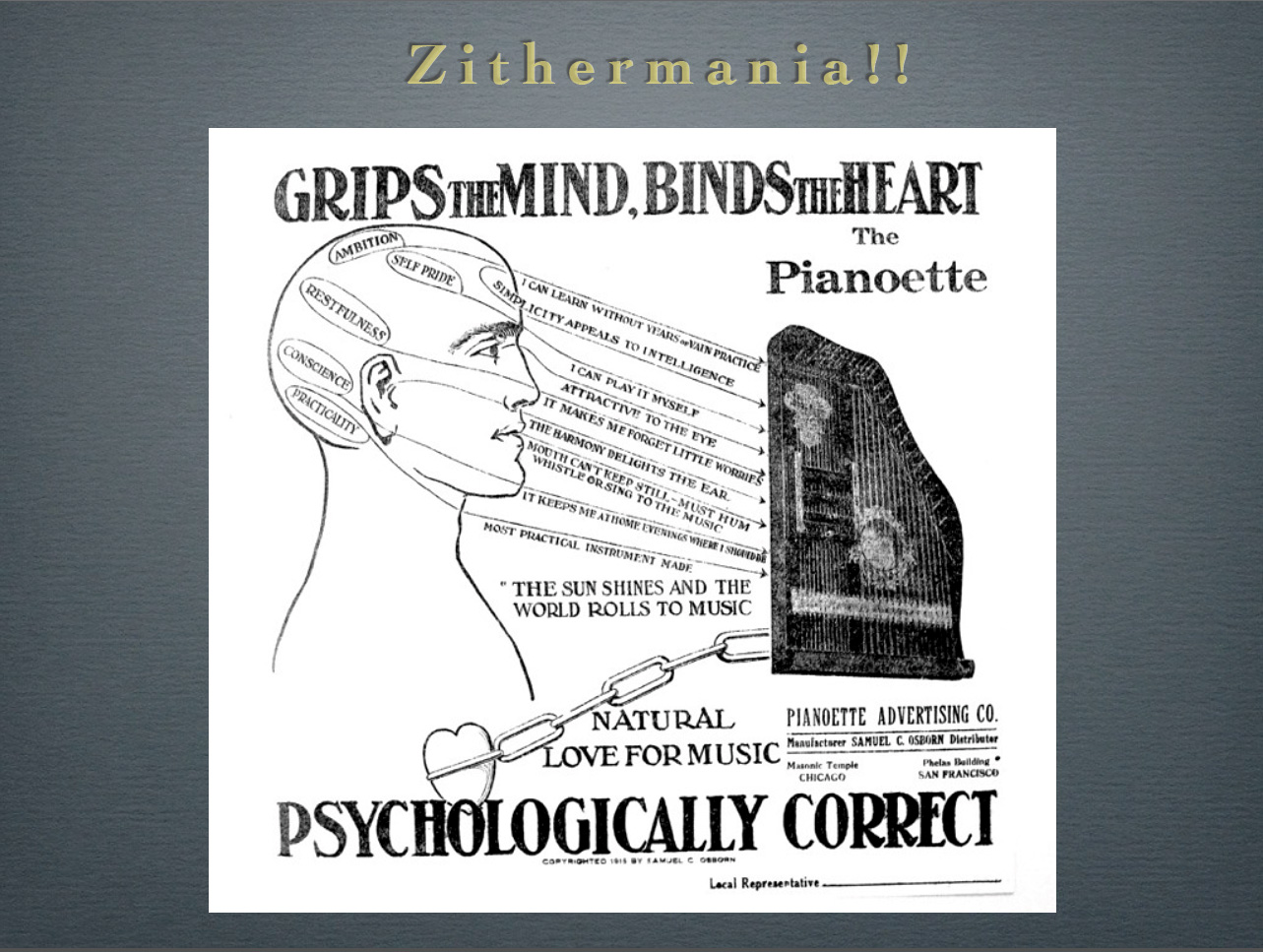

You all know my “fretless zithers” creds. You might remember that my original colleagues Kelly Williams and Garry Harrison (who focused solely on them, where I did not) are long gone – Kelly retired from it, Garry passed away much too early. But a new fellow, Rick Meyers from Portland, has taken up the cause! He did a paper on the Marxochime Company two years ago (I missed that one) and this year presented “Zithermania!!” highlighting some of the NMM’s unprecedented collection of ~500 zithers (mostly fretless), collected and donated by Paul and Jean Christian in 2006. Rick was staying the next week to continue his research and cataloging – there are many variants that none of us had ever seen, including:

A double decker (two levels) chord/melody variant with little sharping cams that can change the pitch a half or whole step. Rick and museum staff just managed to get them to work! This one is a Phonoharp instrument, going under the a.k.a. of “The Harp Guitar Mfg Co.” (and yes, it’s my “Harp Guitars in Name Only” Gallery).

A double decker (two levels) chord/melody variant with little sharping cams that can change the pitch a half or whole step. Rick and museum staff just managed to get them to work! This one is a Phonoharp instrument, going under the a.k.a. of “The Harp Guitar Mfg Co.” (and yes, it’s my “Harp Guitars in Name Only” Gallery).

The fanciest Apollo Harp model, with the never-before-seen “Keyed Slide” attachment that could dampen strings (as in the Autoharp) in enough combinations to yield 72 chords.

The amazing “Cecilian,” a chord zither combined with a miniature bellows reed organ!

…to name just a few.

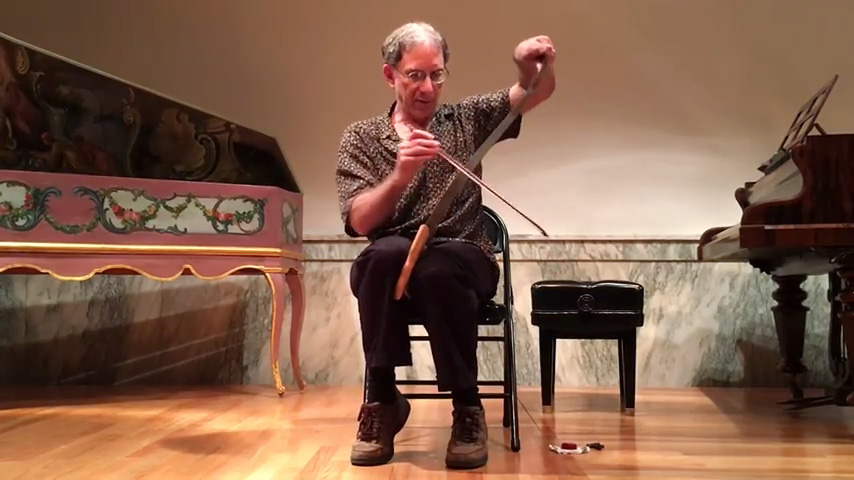

Rick makes his living as a living-history multi-instrumentalist performer-historian. In Hollywood we would call him a “multi-hyphenate.”

Do not miss his short musical saw performance in the video at the end of this blog.

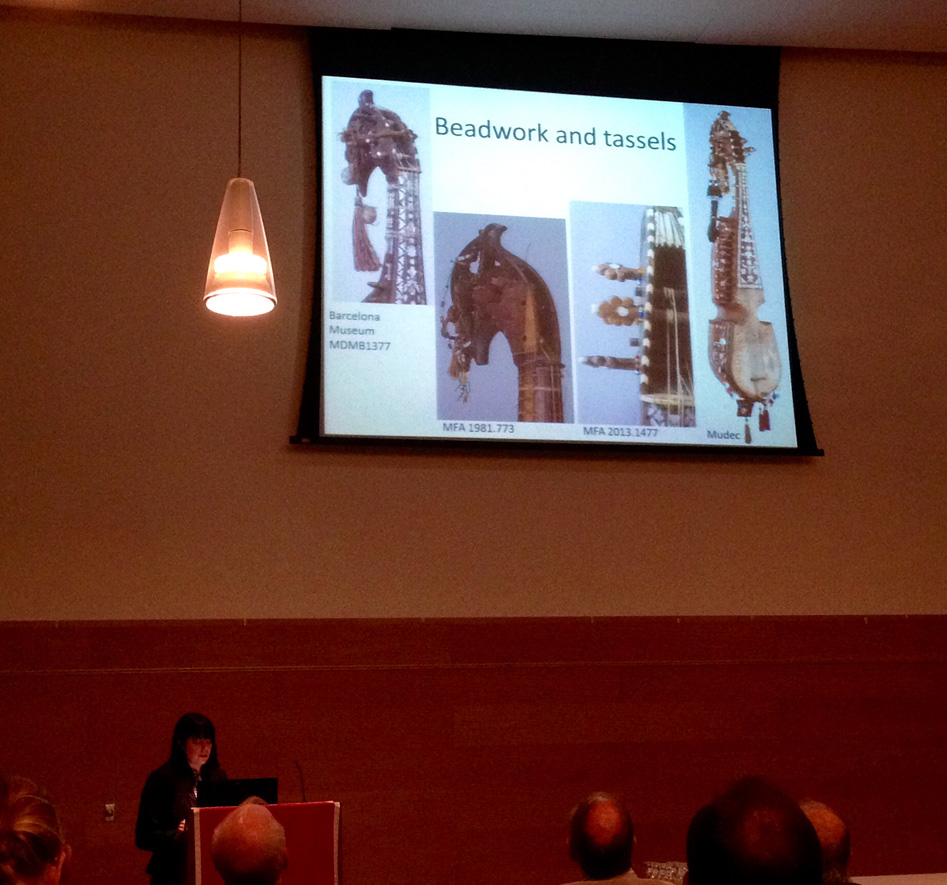

Jayme Kurland from the Boston Museum gave a talk on the Afghan rubab, of which I knew virtually nothing (including how to spell it and how many things called “rabab” there are!). Not seeing my own eBay-purchase version on her list of known specimens, I was curious to ask her about it – and it transpired that she was coming to L.A. to visit friends the very next week! She got the full tour and I had my rubab inspected (or do I need to rephrase that?).

The verdict? Recent, but fairly authentic.

My Australian friend Graham MacDonald (The Mandolin: a History author) gave a paper explaining the main mandolin evolutionary shifts and their tonal effect (bowlbacks > flatbacks being a gross oversimplification, but you get the idea). His audio sample comparing a passage played on a Calace bowlback and a Gibson F5 copy was rather enlightening, but the waveform comparison of specific notes was fascinating. We had a blast hanging out together, and many new people discovered his book (and told me they loved the picture on p.219).

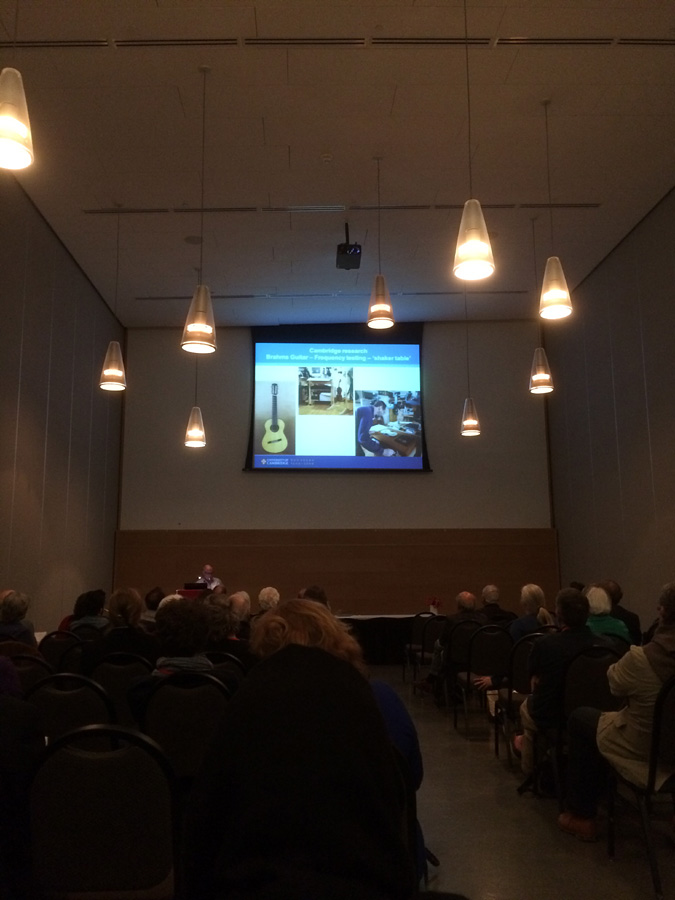

James Westbrook, no stranger to fans of 19th century guitars, gave his paper on the career and instruments of post-war luthier David Rubio, of whom I knew little. From New York jazz and flamenco guitars to Julian Bream’s lutes and guitars (eventually moving on to Bream’s property).

Other obscure things I accidentally learned about during the week were tenoroons, Naust Baroque flute conical bore shapes, the modern bass sheng industry in China (wild!), the action of one of Beethoven’s pianos, a ginourmous Conn sousaphone, Dolmetsch’s early 1900’s “new action” for harpsichord, and the world of English concertinas. Luckily, no pop quiz on any of the above.

I’m hoping all this will inspire more of you to come (and stay awake) for my own measly short harp guitar talk at the next Gathering!

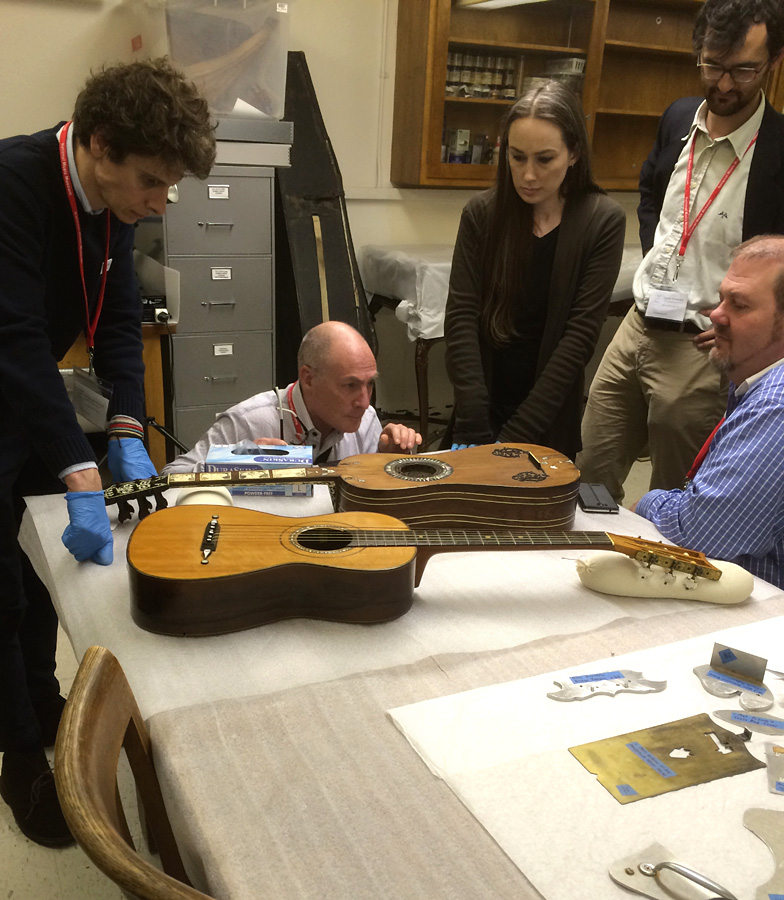

Much additional private discussion and research continued throughout the week. At one point, I was invited to join a small guitar group in the basement as they examined several recent acquisitions:

Inspecting and trying to identify an unmarked Baroque guitar are (l-r) NMM conservator Emanuele Marconi, James Westbrook from England, NMM strings curator Arian Sheets, Daniel Wheeldon (London>Edinburgh>New York Met research fellow) and Matthew Hill (currently in Scotland). An 1836 Panormo is in front.

The former has an unusual and wonderful rosette…

…and delicately engraved fingerboard scenes.

Panormo’s distinctive headstock and beautiful tuners. Jim told us he has had to create replacement pearl buttons (about 3/16” thick!) for a Panormo back home. Behind that is a pile of vintage metal Gibson headstock inlay templates acquired by the museum. Matthew Hill was down there voluntarily cataloging them for the database (this is what true guitar nerds do for fun and relaxation).

Besides all the exhibits, scholarship and study, the organizers also lined up some special outside evening entertainment for us.

The New Custer Brass Band performed compositions and arrangements by Felix Vinatieri, the Chief Musician to General Custer (luckily, the band stayed behind to assist the medics for the Little Bighorn gig, and he survived to tell the tale).

Friday night’s casual banquet included bison barbeque with mac ‘n cheese (only in South Dakota…I went back for thirds) and polka band. It became necessary to flash the x-ray of my heel bone spur to several overly-eager women in order to stay out of the fray (though Kathleen Wiens got me good).

I mentioned last week that several musical performances were given on the museum’s display instruments. Always fascinating to sit and immerse one’s self in, the gamelan orchestra sees regular use by a group of musician volunteers who have become a pretty impressive ensemble…

…which leads off this short YouTube video compiled by Ed Johnson. It includes excerpts of museum gallery performances and a couple from the new AMIS Live! – a sort of “member’s talent show” I was happy to be a part of. There were flutes, trumpets and keyboards, Michael Suing surprised me with his mellifluous baritone, and who knew solo clarinetist Al Rice could rock Stravinsky like that!

For all the prep, organization, near seamless coordination, good food and finagling the campus beer and wine rules to keep me adequately inebriated, I want to congratulate and thank the entire NMM and AMIS staff, and especially the indispensable (if overly shaggy) Michael Suing.

Hope to see you in Edinburgh next year!

Gregg Miner