Nothing makes me cringe more than seeing an otherwise beautiful (not to mention, valuable) Dyer harp guitar that has been badly mistreated or, on occasion, creatively “improved” by some anonymous past owner. I am often advising owners on the merits and options of restoring such instruments versus leaving things “as is.” Which is never trickier than when they are hoping to sell it.

Case in point: A few poor photos came in on the current specimen that barely scratched the surface of the alterations made to it. Had I known what was to come, I probably would have said best not to even send it.

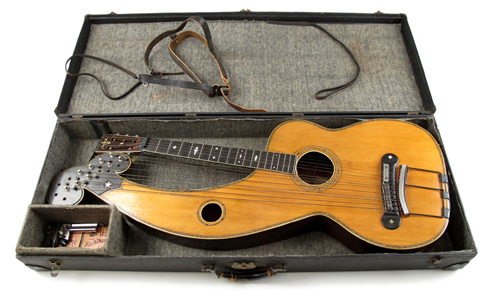

Though I am now glad it came! This once-standard issue Style 7 is past all hope of being restored to fully original condition, but the work that had been done to it, and the mysteries contained therein, were so interesting that I even toyed with the idea of keeping it “as is” for myself. For, let’s face it, how often does one come across a “vintage” Dyer harp steel guitar?!

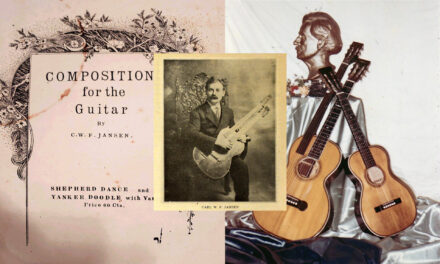

For the uninitiated, “harp steel” is what we now call “harp Hawaiian guitars” – that is, a Hawaiian guitar (played on the lap with a steel slide bar) that has had harp strings added to it. Knutsen was the only one crazy enough to have routinely done this (and now, occasionally, similarly crazy luthier Michael Dunn).

We don’t know who, when or why someone decided to modify this Dyer into a sort of “super harp steel.” It belonged to the previous owner’s father’s late uncle, and the family believes that he had bought it in New York already modified in its present state. No one remembers him playing it (though the modern Dobro steel in the otherwise period case tells us that someone certainly tried to play it more recently). So the original harp steel player’s identity and motivation will sadly remain a mystery. It’s also hard to say how old the work is…40-50 years? Older? Perhaps the action had degraded so much due to the warped top that the person decided to just go “full Dobro”? Or maybe they just weren’t appreciative enough of “a funky old instrument” and thought it would be cool to see what they could make of it. Who knows? (and anyway, who are we to judge?…)

Ready?

The person (I’ll presume it was a “he,” though perhaps it was built for a “she”) was clearly a decent and imaginative machinist.

Here, he raised the fretboard strings up like a Dobro with a new, custom metal nut. Note that it was deliberately made for just 5 strings, as somewhere along the way he had lost a tuner.

He decided to give up on the bridge and instead attached all the strings to the tail block, so created the multiple supports and ball end slots. To reuse the existing saddles, he bolted new plates on to clamp the strings down behind the saddles.

And since he was starting over from scratch, why not add a few more bass strings? From the tailpiece slots, it looks like there were twelve.

But take a look at this puzzle. This seems to show that he may once have planned to add to 14 separate bass strings (?)! Some of the presumed additional tuners and posts are missing. I am certain he originally planned this out carefully, as all the metalwork is precise and deliberate.

Perhaps to cover up the existing holes, perhaps to strengthen the whole area (or both), he added nicely fitted metal plate covers over both sides of the bass headstock. Note how he left a perfect cut-out for the star inlay!

In order to additionally strengthen the neck, he decided to first add a metal overlay there. Nice work!

To this, he attached a rod that went all the way through the body and bolted to the tail block.

But he also affixed it solidly to the bass headstock with this elaborate custom fixture. Talk about an “L” bracket!

The rosettes are unfortunately ruined by a ring of deformed holes – perhaps by taper head screws that once attached something to the openings. Some sort of pickups? Or perhaps some sort of solid plates to close the acoustic openings in an effort to make an electric harp steel?

For he clearly made it electric – as the openings in the new tailpiece demonstrate.

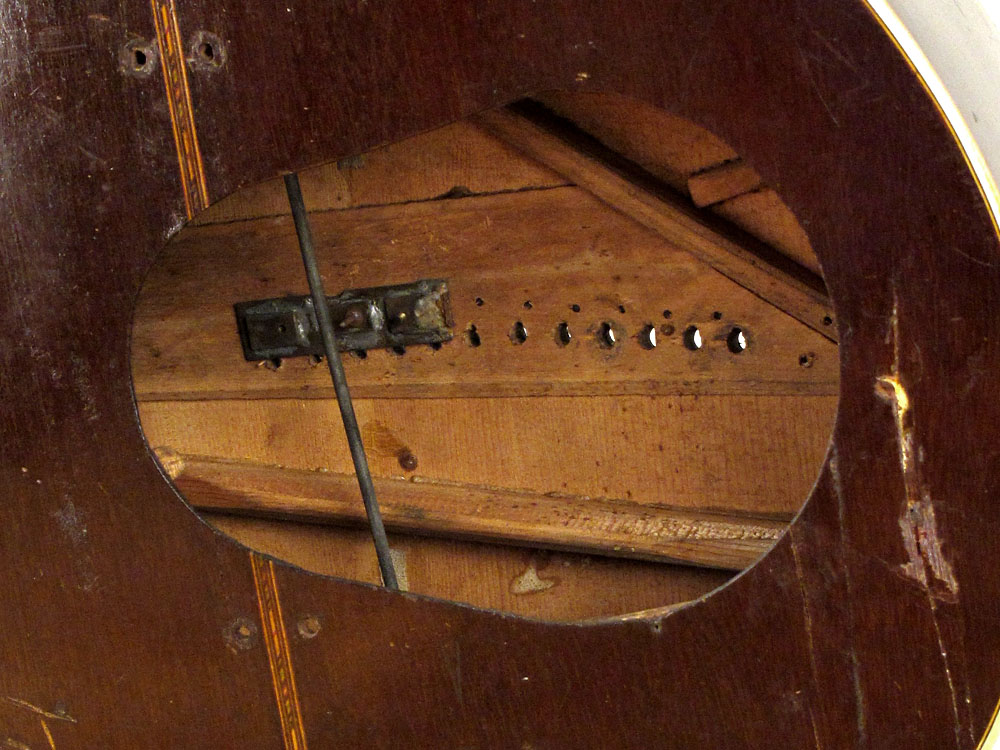

Ouch! Yes, this was the real shocker. That’s one helluva sound port! Cleanly done, this must have been some sort of huge “permanent access panel” to do the modifications. Unless it was meant to stick a big tube mic right inside?

The “extra back” is quite strange…is it a new, extra piece of veneer? No, it seems as if he masked off this seam and put a super thick coat of some type of lacquer on the original back.

Through the gaping opening, one can see the original 6 sub-bass holes, and that he has welded the 6-string clamping plate on from the back.

The tension support rod going through the tail block.

And a new serial number for the growing inventory.

Equally interesting and mysterious are these two custom steel bars that he made. What fingers were they attached to and how? Would they be used in lap position or Spanish position? Could they have been intended to be worn simultaneously on a finger and the thumb? The finger loops are quite small, and so is the lone fingerpick – so the player certainly had small or slender fingers.

They (he or she) also must have had a very small waist, judging by what I think is the “belt” portion of the crazy horse-bridle-like strap invention. It looks like it was designed so you could strap the instrument on and play standing up.

I would kill to have seen this thing in action, wouldn’t you? Almost makes all the Frankensteining forgivable!

Speaking of which, it’s now in private hands again, for a potential long-term restoration project. Here’s the first step: removing the bass coverplate…surprise!

But while I certainly don’t envy the new owner, I do admire the creativity of our mysterious harp steel inventor!

Gregg,

Thanks for sharing. I think I am going to be sick.

Don

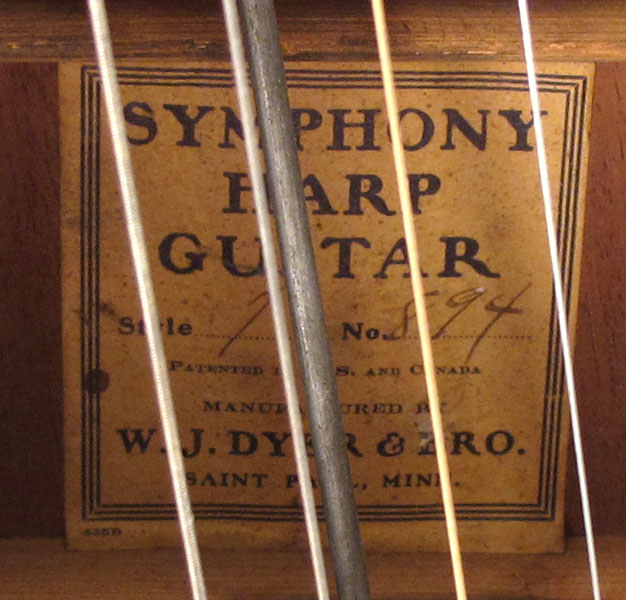

Bob – you’re right! We since re-sold Stacy’s “894”. Here is the best image I have of the label:

https://www.harpguitars.net/history/dyer/894b.jpg

It’s possible that that is a sloppy “7”?

Unfortunately, we also have a Style 4 as “874” in the list – so perhaps THAT one is also a mis-read? (“4″s are notoriously sloppy).

We’re going in circles!

Hello mr.Gregg.

Thank you for your sharing to these photographs.

I had been thinking about a thing same as this report to remodel my Koto-harp guitar.

Ok everyone on the list give 1$ to hire a soprano to take “care” of the butcher…

What a nightmare !!!!!!!!!!!!!

This person really missed the boat. There are no side sound ports!

This serial number is on my list for a style 5 formally owned/seen by The Pope and Stacy Hobbs.

This label number is quite clear and maybe the other one was not.